Toroids with many turns of secondary winding are very useful for AC current sensing and measurement because you can just pass the wire carrying the current to be measured thru them. (We’re not talking about coils with a couple of wimpy turns for RF – though those can be a good source of cores.)

Toroids with many turns of secondary winding are very useful for AC current sensing and measurement because you can just pass the wire carrying the current to be measured thru them. (We’re not talking about coils with a couple of wimpy turns for RF – though those can be a good source of cores.)

But unless you can find a good, cheap source of well-wound toroids, you’re faced with the really unpleasant task of threading hundreds of turns of fine wire through that core. (Well, unpleasant unless you have one of these cool toroid winding machines. But I don’t.)

After I finally figured out how the machines work, I thought about building one. But there are too many strange and precision parts, especially if you want to wind small cores – which I do. So how do you quickly and simply wind wire on a closed loop toroid?

Cutting

Well, duh – you cheat. If it’s good enough for Captain Kirk… The idea is to cleanly split the toroid in half, wind it, then put it back together. Yeah, it’s magnetically not quite as good after you glue it back together, but it’s good enough.

Fortunately, a ferrite core is kind of brittle, and if you score it nicely, it will often break fairly  cleanly. I’ve tried a couple of different ways to score them, with varying results. The first was to just saw halfway thru before cracking it. (The material cuts very nicely with a hacksaw.) That approach provided a nice break, but lost so much material that it really felt like performance of the core would be compromised. (I never bothered to wind it.)

cleanly. I’ve tried a couple of different ways to score them, with varying results. The first was to just saw halfway thru before cracking it. (The material cuts very nicely with a hacksaw.) That approach provided a nice break, but lost so much material that it really felt like performance of the core would be compromised. (I never bothered to wind it.)

In the spirit of scoring

In the spirit of scoring  plastic, I tried a Stanley knife. It felt like it didn’t go deep enough to guide the break as much as I wanted. A triangular file didn’t have any trouble cutting the material, but made a wider score than I wanted. In any event, scoring the outside (and inside!) edges, as well as the flat side might help guide the break better.

plastic, I tried a Stanley knife. It felt like it didn’t go deep enough to guide the break as much as I wanted. A triangular file didn’t have any trouble cutting the material, but made a wider score than I wanted. In any event, scoring the outside (and inside!) edges, as well as the flat side might help guide the break better.

I generally held the core in a vise and whacked it to effect the

I generally held the core in a vise and whacked it to effect the  break. Results varied from about perfect to needing some additional reassembly.

break. Results varied from about perfect to needing some additional reassembly.

The material’s clean breaks make super glue appropriate. By clamping the pieces together tightly, the gap  should be small enough to not hurt the magnetic properties too much. When there are chips, it may be easier to glue the chips back carefully as a separate step before you put the two halves back together. If there are chips missing, abort and try a new core. An air gap in the core is exactly what you DON’T want.

should be small enough to not hurt the magnetic properties too much. When there are chips, it may be easier to glue the chips back carefully as a separate step before you put the two halves back together. If there are chips missing, abort and try a new core. An air gap in the core is exactly what you DON’T want.

Winding

While you could wind the secondary by hand, my strong first choice would be to let  a drill or something turn the core while I guide the wire. We’ll need to attach some kind of spindle to the core to do that. Most of the winding will be about midway between the two breaks, so that part should be on the centerline of the spindle to minimize wobbling.

a drill or something turn the core while I guide the wire. We’ll need to attach some kind of spindle to the core to do that. Most of the winding will be about midway between the two breaks, so that part should be on the centerline of the spindle to minimize wobbling.

You could use a dowel nicely shaped concave to fit up against the core as  the spindle, but the bottom would probably (underlap?) interfere with some of the windings. Some copper or aluminum tubing lets you take advantage of the part of the core that won’t get any wire as a glue surface. If you handle it gently while winding, hot melt is a great way to hold the spindle to the core half temporarily.

the spindle, but the bottom would probably (underlap?) interfere with some of the windings. Some copper or aluminum tubing lets you take advantage of the part of the core that won’t get any wire as a glue surface. If you handle it gently while winding, hot melt is a great way to hold the spindle to the core half temporarily.

Clip of live winding

It’s nice to know about how many turns you’ve put on so you can confidently make an identical one or vary the number of turns as you experiment. Having a helper to count the turns is convenient. Another, probably less accurate approach is using an estimate of the average diameter of one turn of the winding and the desired turn count to compute how much wire it will take. Pre-measure the wire, and when you run out, you’re done. In any event, chuck the spindle in a drill, tie off some wire so you’ll have a nice lead to work with and start winding! Thanks to Ti Leggett at Workshop 88 for the video. It’s also posted on the W88 blog.

Unlike with some fussy RF coils where you have to worry about losses distributed through the bulk of the core, it doesn’t really matter where on the core your secondary windings are. Having them all bunched up together is fine. But if you’d like to spread them out a little more (perhaps to leave more room for the primary wire in a very small core), it seems like if the drill/whatever is turning slowly enough, you should be able to move your wire-guiding hand back and forth in sync with the rotation such that the extended edges of the winding were neatly wrapped square around the core like the ones in the middle. I’ve tried it, but with only very limited success.

Putting it back together

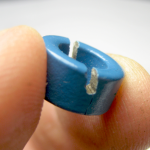

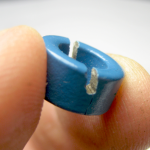

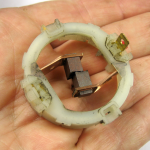

Super glue seems good because the breaks are clean and it introduces such a minimal gap at the joints. Here’s a 1″ O.D. core wound with 200 turns of #30 magnet wire and glued back together. Something like epoxy, that provides filler and some thickness to the glue joint would require that you clamp the core halves together quite tightly to squeeze out as much glue as possible.

Super glue seems good because the breaks are clean and it introduces such a minimal gap at the joints. Here’s a 1″ O.D. core wound with 200 turns of #30 magnet wire and glued back together. Something like epoxy, that provides filler and some thickness to the glue joint would require that you clamp the core halves together quite tightly to squeeze out as much glue as possible.

If you’d like a little more physical strength and robustness – perhaps for a current transformer you were going to put around the main AC feed wires in your breaker panel – one possible approach would be to include a narrow zip tie on the outside of the core under the winding before you wind it. After you glue the core halves together, bring the ends of the zip tie around the top of the core and pull it tight. If you were quick, it could even provide clamping while the glue dried. (Sorry – no picture. I’ve never tried it.)

Now what?

You must have had some reason to wind that coil in the first place. If it’s for a current transformer to measure AC current, you’ll need to terminate the secondary in a very low resistance, and figure some way to measure the secondary current. You’ll probably also need to do some calculations (or at least testing) based on the material and dimensions of the core to see if it will stay linear (not saturate the core) over the current range of interest.

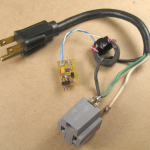

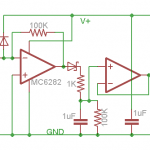

If you just need to sense AC current – for some kind of logging or perhaps automatically turning one device on when another is on, you can probably get away with most any small core. Here’s a note on how I built an interface to an Arduino.

And if you wound wire on both halves of the core, you could make a more traditional transformer. I’ve never tried that.

Good luck with your new toroid!

Update 2/14/13: The W88 blog post made it to Hackaday! The commentors there always keep people honest, and this was no exception. One poster said he had broken cores several times, and there was no way to get the core back together tight enough. He indicated his cores lost an order of magnitude in inductance! I had no quantitative handle how much the gluing cost, but I didn’t think it would be that much. Time to try to measure the reduction I’m seeing.

I hand wound exactly 30 turns on one of the same cores (without breaking it first). I tried a couple of indirect ways to measure the inductance, since I don’t have an inductance meter. (I do have a capacitance meter, and tried using that both by switching the test leads and even by rotating the meter 180 degrees, but neither one worked.)

Extrapolating from the 30- to the 200-turn coil

The first thought was to measure the inductance of the intact 30 turn test toroid and compare it to the 200 turn glued-together toroid. Since inductance is proportional to the square of the number of turns, I would expect the inductance of the big coil to be about (200/30)²=44.4 time that of the small coil.

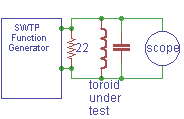

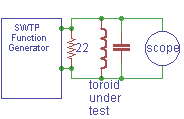

I tried making a tank with a 47 nF cap in parallel with the coil, driving it with my dear old (old being an operative term) Southwest Technical Products function generator and looking at it with a scope. (The 22 Ω across the generator output was to lower the output impedance from I think 75 Ω.) I was going to use the known cap and the resonant frequencies to compute and compare the inductances of the large and small coils. I aborted this after I realized this added a new variable of frequency, and I had no idea how the toroid material behavior changed with frequency.

I tried making a tank with a 47 nF cap in parallel with the coil, driving it with my dear old (old being an operative term) Southwest Technical Products function generator and looking at it with a scope. (The 22 Ω across the generator output was to lower the output impedance from I think 75 Ω.) I was going to use the known cap and the resonant frequencies to compute and compare the inductances of the large and small coils. I aborted this after I realized this added a new variable of frequency, and I had no idea how the toroid material behavior changed with frequency.

Update: The setup above is just wrong. There should be some resistance in series with the tank to see the resonance clearly. Thanks to M Peters for his comment below.

To eliminate the frequency variable, I found resonance with the large coil and 1 μF at just about 2 KHz. I changed to the small coil and tried different cap values until I got resonance at 2 KHz again. That was adding a 10 μF electrolytic across the 1 μF film cap for around 11 μF. Plugging those values into a nice LC resonance calculator gives inductances of 570 μH for the small coil and 6300 for the large one. That’s hardly the expected factor of 44, and using the test of a factor of √10, is in fact (barely) an order of magnitude off. But the methodology was poor: Twisting a knob and looking for a peak magnitude on a scope for a low-Q circuit is hardly precise. And electrolytic caps have notoriously inaccurate values at best, and using them at zero volts is completely out of spec. Next approach?

Apples and apples

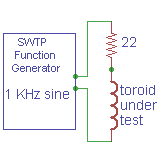

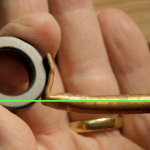

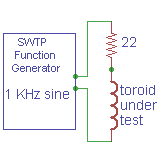

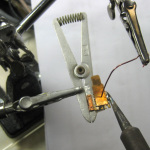

The best approach would be to get something with the 30 turn coil I could measure with a decent meter, break and glue it, and measure again. I put a nice carbon resistor in series with the coil, cranked the signal generator to 1 KHz, and measured the voltage across the resistor and the coil with a multimeter whose AC ranges were known good for that frequency.

The best approach would be to get something with the 30 turn coil I could measure with a decent meter, break and glue it, and measure again. I put a nice carbon resistor in series with the coil, cranked the signal generator to 1 KHz, and measured the voltage across the resistor and the coil with a multimeter whose AC ranges were known good for that frequency.

I scored the coil with a jeweler’s file and broke it. The break was one of the cleanest I’ve had (fortunately). I used some old (read: thicker than expected) no name cyanoacrylate, wiggled the pieces to be sure they seated as well as possible, squeezed hard and put a spring clamp on it. Then I put it back in the test circuit.

I scored the coil with a jeweler’s file and broke it. The break was one of the cleanest I’ve had (fortunately). I used some old (read: thicker than expected) no name cyanoacrylate, wiggled the pieces to be sure they seated as well as possible, squeezed hard and put a spring clamp on it. Then I put it back in the test circuit.

The break/glue happened over maybe 5 minutes, and the test setup was untouched, including the signal generator. I measured the voltages across the resistor and coil again. (Twice for each, as I had done the first time.) This is about as clean a comparison as I can make. So at 1 KHz with a 22 Ω resistor here are the results:

Vres Vcoil Zcoil L

Before 0.367 0.097 5.81Ω 925μH

After 0.372 0.068 4.02Ω 640μH

The inductance is reduced by the gluing by about 30%. Quite noticeable, but quite acceptable for a hack.

I also did measurements of the tank circuit resonant frequency with the parallel combo of 10 μF electrolytic + 1 μF film caps before and after the break. While there is a frequency difference, I’d guess it doesn’t contribute a large error.

freq L

Before 2.0 KHz 576μH

After 2.7 KHz 316μH

That test indicates a 45% decrease in inductance. Not identical, but in the same ball park. Now we have a rough quantitative handle on the impact of break/glue.

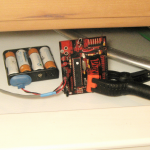

I’ve used my 18V B&D cordless blower to clean grass clippings off the sidewalk after mowing for many years. It’s great. The 15 cell sub-C NiCd battery packs didn’t last for a whole cleanup – but I had two, rebuilt them, and limped along. Then I hacked the nice 3.3 A-hr Li-ion pack in and it would run 2 or 3 cleanups between recharges. Great! (OK, and ugly. But it works.)

I’ve used my 18V B&D cordless blower to clean grass clippings off the sidewalk after mowing for many years. It’s great. The 15 cell sub-C NiCd battery packs didn’t last for a whole cleanup – but I had two, rebuilt them, and limped along. Then I hacked the nice 3.3 A-hr Li-ion pack in and it would run 2 or 3 cleanups between recharges. Great! (OK, and ugly. But it works.) broom, grumble… After sweeping up, I checked and there was in fact voltage at the connector into the blower. (While the original plan was to fit the Li-ion into one of the old battery pack shells (though sticking out one end), all I ended up keeping was the connector from the old pack. It’s connected to banana plugs that mate with the battery with a piece of 18-2 zip cord. That wire’s not really big enough – it gets warm when the blower runs for more than a minute or so.)

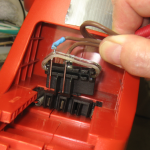

broom, grumble… After sweeping up, I checked and there was in fact voltage at the connector into the blower. (While the original plan was to fit the Li-ion into one of the old battery pack shells (though sticking out one end), all I ended up keeping was the connector from the old pack. It’s connected to banana plugs that mate with the battery with a piece of 18-2 zip cord. That wire’s not really big enough – it gets warm when the blower runs for more than a minute or so.) Great – did running a motor designed for 18V NiCds on a hot 18.5V Li-ion burn out the brushes? It’s noticeably louder (and higher pitched and more effective!) with the new battery. So I took it apart, and the problem was immediately clear: One of the motor wires was disconnected.

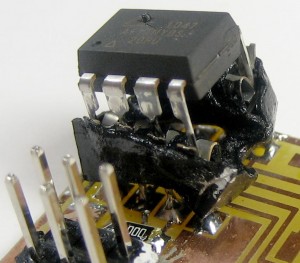

Great – did running a motor designed for 18V NiCds on a hot 18.5V Li-ion burn out the brushes? It’s noticeably louder (and higher pitched and more effective!) with the new battery. So I took it apart, and the problem was immediately clear: One of the motor wires was disconnected. Worse: The terminal going into the motor was broken off below the surface. There’s really no way to fix that from the outside, and with the stamped/crimped construction of the motor, there was no simple way to take it apart. Rats.

Worse: The terminal going into the motor was broken off below the surface. There’s really no way to fix that from the outside, and with the stamped/crimped construction of the motor, there was no simple way to take it apart. Rats. With nothing to lose, I started trying to tear it apart in a way that might let me put it back together in case I figured out a way to actually fix that terminal.

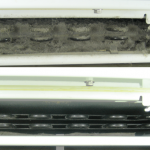

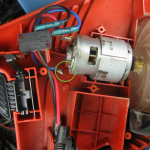

With nothing to lose, I started trying to tear it apart in a way that might let me put it back together in case I figured out a way to actually fix that terminal. The end of the motor shell is crimped around the end plate. It’s steel and bent away only grudgingly to some end nippers. But bend it did, and the end plate (and bushing) came right out.

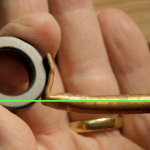

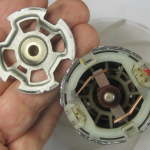

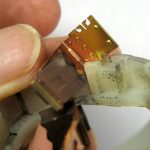

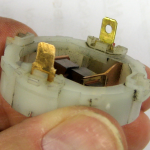

The end of the motor shell is crimped around the end plate. It’s steel and bent away only grudgingly to some end nippers. But bend it did, and the end plate (and bushing) came right out. The remaining terminal is attached to a plastic brush holder ring.

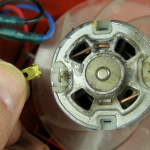

The remaining terminal is attached to a plastic brush holder ring.  That pulled right out, too. The brass terminal piece is riveted to the brush spring, and fits through a slot in the plastic ring. There was so little surface area where the terminal was broken off that there was no hope of

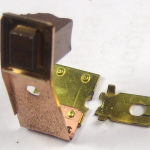

That pulled right out, too. The brass terminal piece is riveted to the brush spring, and fits through a slot in the plastic ring. There was so little surface area where the terminal was broken off that there was no hope of  reattaching it short of brazing, which I wasn’t comfortable with and might have hurt the brush spring.

reattaching it short of brazing, which I wasn’t comfortable with and might have hurt the brush spring. 0.020″, but I guessed it would work if I smushed the female terminal a little. Whether it ever gets hot enough to melt the solder is a good question. I tinned both surfaces first, made a jig to hold them together and sweated them. An aluminum clamp heat sink was there to try to protect the brush spring.

0.020″, but I guessed it would work if I smushed the female terminal a little. Whether it ever gets hot enough to melt the solder is a good question. I tinned both surfaces first, made a jig to hold them together and sweated them. An aluminum clamp heat sink was there to try to protect the brush spring. It was obviously thicker overall than the original, but to my surprise took only a little forcing to fit into the original slot. Looks promising!

It was obviously thicker overall than the original, but to my surprise took only a little forcing to fit into the original slot. Looks promising! When I went to crush the female terminal to fit the thinner male, I was quite surprised to find solder blobs on both females. I have no idea what that’s about.

When I went to crush the female terminal to fit the thinner male, I was quite surprised to find solder blobs on both females. I have no idea what that’s about. but you can see the cross section of the out-of-focus brush in the foreground in the picture above of how the terminal fits in a slot in the plastic ring.

but you can see the cross section of the out-of-focus brush in the foreground in the picture above of how the terminal fits in a slot in the plastic ring. prettier. The brush holder and brushes slipped right in, along with the metal end plate. Some creative placement on the anvil let me peen the crimped edges back over the end plate. It came out pretty well.

prettier. The brush holder and brushes slipped right in, along with the metal end plate. Some creative placement on the anvil let me peen the crimped edges back over the end plate. It came out pretty well.